Imagine you have a favorite recipe for making cookies. You learned it from your grandmother, and you have always made cookies this way. You think they're the best dessert in the world, and people regularly compliment you on them when you bring them to parties. You understandably take great pride in your baking -- but would you insult someone else's cookies, or denounce their recipe as illegitimate?

One hopes the answer would be no, but people take this attitude towards other people's language every single day. As I've argued before, anything that someone says or writes on purpose is a correct use of language, just like every cookie recipe out there is a correct use of baking. Unfortunately, some uses of language are often considered incorrect, and I think there are two main reasons for that.

First, although most of us are probably tolerant of variation among baked goods, there does seem to be a natural tendency for people to assume that their way of doing something is the only right way -- and to believe by extension that all other possibilities in that mode are wrong. This tendency is compounded if someone knows a lot of other people who do things the same way as them, since we tend to look to those around us for verification that we're in the right. So if you and your friends would never say “ain’t,” for example, it’s very easy to conclude that “ain’t” isn’t a correct use of language. But that claim is a subjective opinion, not an objective fact. At its core, it’s just like saying that your grandmother’s recipe is the only correct way to make cookies. The fact that you might call my recipe wrong doesn’t mean that it really is incorrect; it just means you’re judgmental about cookies.

The second reason is that historically, people have listened to the haters, and written down their opinions in books that market themselves as holding facts. So there’s a widespread belief in the world today that some forms of language are wrong, because textbooks and dictionaries and Microsoft Word’s spellcheck all say so. But even if all of the cookbook writers in the world liked your grandmother’s recipe and printed scathing condemnations of my own, that wouldn’t make my cookies any less legitimate. They’d still be valid as cookies, and I’d be well within my rights to prefer them to yours.

As a linguist, I make it my job to look at language as it exists in the world and draw conclusions about it based on what I see. Imagine if I was trying to do that with cookies: examining individual cookies to learn more about the nature of that dessert. My report would be a lot poorer if I listened to people saying, “Don’t bother with those ones — they aren’t real cookies. Eat all the ones in this batch instead.” Indeed, I might easily overgeneralize, making conclusions like, “All cookies have chocolate chips in them,” and I might unknowingly leave things like Oreos out of my account of the various forms a cookie can take. If my job was to accurately describe the snack, I wouldn’t be doing a very good job of it.

The reason I react so strongly against judgments on language is that, unlike with cookies, most of the world doesn’t really understand that language isn’t a matter of right and wrong. Prescriptive grammar (saying what’s right and what’s wrong in language) has a long history in our society, and it’s going to take some real effort on the part of people who know the facts to overturn that myth’s hold on people’s minds. And also unlike cookies, language is something that most people feel very strongly about. Language is often a reflection of a person’s identity in some form or another, far more than a recipe is, and people can be very hurt by the allegation that their language is incorrect or shame-worthy. It feels like a personal attack, and to some extent it is —- especially because judgments on language often mask judgments on other factors of a person’s identity, such as gender, race, or age.

There's also the simple fact that I think diversity is beautiful. I think the world is a much tastier place the more recipes are represented in it, and language is no exception to that.

This is not to say that you have to stop liking your grandmother's cookies, or start liking oatmeal raisin. In language or in baking, it's fine to have preferences of things you like and dislike (although I think it can be revealing to investigate where those preferences come from). It’s just not fair to dismiss the things you don’t like as illegitimate, or to assert that no one else is allowed to like them either. It’s true of cookies, it’s true of music, and it’s true of language: we don’t all have to like the same things, but we should all respect the tastes that other people do have.

Language Hippie

Wednesday, April 11, 2012

Wednesday, March 14, 2012

Someone asked me about 'singular they,' and this is what I told them

If you are a native speaker of English, it's very likely that nothing in the title of this post struck you as unusual -- and yet, it contained a form that many English teachers would wholeheartedly denounce. This form is known as 'singular they,' and although it's a linguistic feature that many English speakers employ conversationally, it is often attacked as incorrect, particularly when it shows up in writing. Essentially, singular they refers to the use of the plural pronoun “they” (as well as “them” and “their”) to refer to a single person. It’s controversial because some people think these words should only ever be used to refer to more than one individual.

So, is it truly unacceptable? As usual, I have a short answer and a long answer to this question. The short answer is of course not, because language doesn’t work that way. As I've discussed in other posts on this blog, no linguistic form is inherently unacceptable. Anything that a speaker intentionally produces is grammatical for them, and successfully serves the primary purpose of language: to communicate ideas with other people.

For the long answer, we'll need to look at the many, many reasons why singular they is a regular -- and useful! -- part of the standard English language.

First of all: even calling this pronoun use ‘singular’ is overlooking the fact that the pronoun is still grammatically plural. This can be seen in the verb agreement in the following standard English sentences:

The ‘singular they’ in Sentence 3 is grammatically plural, because it is the subject of the verb "come" and that verb is inflected for a plural subject. If "they" in Sentence 3 were grammatically singular, that verb would be in the singular agreement form "comes" as in Sentence 1. So using a ‘singular they’ is not violating any grammatical rules of subject-verb agreement in standard English, and it is not changing the pronoun from a singular paradigm to a plural one. All that has changed is the referent of the pronoun.

So, is there a problem with plural-marked noun phrases having singular referents? Let's take a look at the subjects in the following standard English sentences, each of which refers to a single entity but is grammatically plural (as can be seen by the verb agreement):

Standard English also has some plural-marked nouns with singular referents that are grammatically singular:

And plenty of singular-marked nouns with plural referents:

Not only that, but there’s variation across countries. The subjects in the above two sentences were grammatically singular, but the following sentences, which are regular in some dialects of British English, have singular-marked nouns with plural referents that are grammatically plural:

The conclusion of all this is simple. There may be a tendency in standard English for referent, form, and grammatical agreement to match one another in number, but there are plenty of cases where this is not true. One can hardly object to the plural pronoun "they" referring to a singular individual without also objecting to the above instances.

Second, singular they is highly useful. The other third-person singular pronouns in standard English require their speaker to make a comment about the gender of the referent, identifying that person as either masculine or feminine. And although it might not seem obvious at first, there may be many reasons why a speaker would not wish to do so. For example, the speaker may not consider the person’s gender relevant to the present discussion, or they may know that the person does not self-identify within the traditional male-female gender binary (and may thus be uncomfortable being labeled as "he" or "she"). When I find singular they most useful, however, is when the referent’s gender is simply unknown. Consider again the following sentence:

In this case, the speaker does not know who left the bag on the table. If we couldn’t use singular they as I have done above, we would have to refer to this person in one of the following ways:

Sentence 12 and 13 assert a gender that is not actually known to the speaker, and may thus be inaccurate. There is also an argument that that sort of sexist language — that is, treating people of an unspecified gender as a certain gender by default — encourages sexist thinking, and we probably want to avoid that when we can. Sentences 14 and 15 are less inaccurate as well as less sexist, but far more cumbersome to say or write than the elegant singular they.

Finally, I’ll bring my argument in favor of singular they back around to usage. Many, many speakers of English utilize this feature in their spoken and written language. If we want to be good scientists, we need to adopt an objective, descriptivist approach to language, and view it as it is actually spoken rather than as we might want it to be. Singular they is out there in the language — and it has been for quite some time. I’d invite you, in closing, to consider one last example sentence. This one was written in 1595 by a Mr. William Shakespeare, in his play Romeo and Juliet:

Juliet doesn’t know the identity of the person on the other side of her door, and thus she doesn’t know the gender either. Her solution is the same one that many speakers would adopt today: she uses the grammatically plural pronoun "they" to refer to a single individual.

So, is it truly unacceptable? As usual, I have a short answer and a long answer to this question. The short answer is of course not, because language doesn’t work that way. As I've discussed in other posts on this blog, no linguistic form is inherently unacceptable. Anything that a speaker intentionally produces is grammatical for them, and successfully serves the primary purpose of language: to communicate ideas with other people.

For the long answer, we'll need to look at the many, many reasons why singular they is a regular -- and useful! -- part of the standard English language.

First of all: even calling this pronoun use ‘singular’ is overlooking the fact that the pronoun is still grammatically plural. This can be seen in the verb agreement in the following standard English sentences:

1. Bill left his bag on the table, and I hope he comes back for it.

2. Some students left their bags on the table, and I hope they come back for them.

3. Some student left their bag on the table, and I hope they come back for it.

The ‘singular they’ in Sentence 3 is grammatically plural, because it is the subject of the verb "come" and that verb is inflected for a plural subject. If "they" in Sentence 3 were grammatically singular, that verb would be in the singular agreement form "comes" as in Sentence 1. So using a ‘singular they’ is not violating any grammatical rules of subject-verb agreement in standard English, and it is not changing the pronoun from a singular paradigm to a plural one. All that has changed is the referent of the pronoun.

So, is there a problem with plural-marked noun phrases having singular referents? Let's take a look at the subjects in the following standard English sentences, each of which refers to a single entity but is grammatically plural (as can be seen by the verb agreement):

4. My glasses are on the nightstand.

5. These scissors are sharp!

Standard English also has some plural-marked nouns with singular referents that are grammatically singular:

6. Checkers is my favorite game.

7. Measles is a terrible disease.

And plenty of singular-marked nouns with plural referents:

8. The army has defeated the enemy.

9. This band sounds awesome.

Not only that, but there’s variation across countries. The subjects in the above two sentences were grammatically singular, but the following sentences, which are regular in some dialects of British English, have singular-marked nouns with plural referents that are grammatically plural:

10. The gang are protecting their turf.

11. The committee meet once a week.

The conclusion of all this is simple. There may be a tendency in standard English for referent, form, and grammatical agreement to match one another in number, but there are plenty of cases where this is not true. One can hardly object to the plural pronoun "they" referring to a singular individual without also objecting to the above instances.

Second, singular they is highly useful. The other third-person singular pronouns in standard English require their speaker to make a comment about the gender of the referent, identifying that person as either masculine or feminine. And although it might not seem obvious at first, there may be many reasons why a speaker would not wish to do so. For example, the speaker may not consider the person’s gender relevant to the present discussion, or they may know that the person does not self-identify within the traditional male-female gender binary (and may thus be uncomfortable being labeled as "he" or "she"). When I find singular they most useful, however, is when the referent’s gender is simply unknown. Consider again the following sentence:

3. Some student left their bag on the table, and I hope they come back for it.

In this case, the speaker does not know who left the bag on the table. If we couldn’t use singular they as I have done above, we would have to refer to this person in one of the following ways:

12. Some student left his bag on the table, and I hope he comes back for it.

13. Some student left her bag on the table, and I hope she comes back for it.

14. Some student left his or her bag on the table, and I hope he or she comes back for it.

15. Some student left that student’s bag on the table, and I hope that student comes back for it.

Sentence 12 and 13 assert a gender that is not actually known to the speaker, and may thus be inaccurate. There is also an argument that that sort of sexist language — that is, treating people of an unspecified gender as a certain gender by default — encourages sexist thinking, and we probably want to avoid that when we can. Sentences 14 and 15 are less inaccurate as well as less sexist, but far more cumbersome to say or write than the elegant singular they.

Finally, I’ll bring my argument in favor of singular they back around to usage. Many, many speakers of English utilize this feature in their spoken and written language. If we want to be good scientists, we need to adopt an objective, descriptivist approach to language, and view it as it is actually spoken rather than as we might want it to be. Singular they is out there in the language — and it has been for quite some time. I’d invite you, in closing, to consider one last example sentence. This one was written in 1595 by a Mr. William Shakespeare, in his play Romeo and Juliet:

16. Arise; one knocks. / ...Hark, how they knock!

Juliet doesn’t know the identity of the person on the other side of her door, and thus she doesn’t know the gender either. Her solution is the same one that many speakers would adopt today: she uses the grammatically plural pronoun "they" to refer to a single individual.

Saturday, March 3, 2012

Hippie Responses

First of all, I want to give a big shout-out and thank-you to fellow linguist Jodie Martin for her wonderful slide show, "So you know a linguist." This short presentation has been passed around a lot on the internet lately, and it does a great job of introducing the field of linguistics to people who might not know much about it. It also makes two points that I especially love: that most linguists would not identify as "grammar nazis" and that we should instead be thought of as language hippies. You can guess why I liked that part!

And it's true: we are scientists of language, but we are also its most fervent admirers: the ones who, as Jodie says, "get REALLY excited over an aspirated p, or the history of a word, or using 'Dude' as a gender-neutral greeting." That's why we don't judge forms that aren't in line with the standard. From our perspective, that unusualness just makes them cooler! Jodie's slides make this point quite clearly and humorously, while also sharing a little bit more detail about some of the particular cool things that we study.

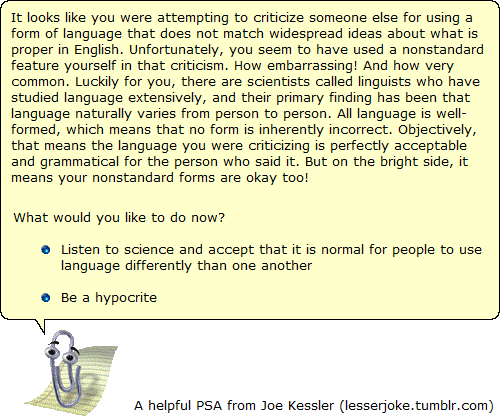

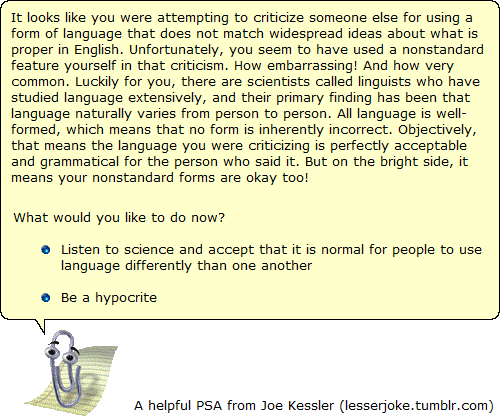

Speaking of responses, I also wanted to share the following image, which I originally made for use on Tumblr. (I'll try to be better about keeping this site updated, but I've been doing a lot of my language blogging on Tumblr in recent months. It enables a much more immediate and back-and-forth conversational style than the comment space on a traditional blog like this one. Whether you have an account with Tumblr or not, you can follow me there at lesserjoke.tumblr.com. Keep in mind that I don't always blog about language, though!) Here's the image, designed to look like a notification from the old Microsoft Word Assistant, Clippy the Paperclip:

I think this image speaks for itself, but I made it to respond to the many, many people who criticize someone else's nonstandard language, only to use one or more forms in that criticism that are nonstandard themselves. Of course, I think language criticism is baseless even when it's formed entirely in the standard, but I've been astonished lately at how often I've been seeing sentiments like this one: "Any college graduate who doesn't know proper English should forfeit their degree." If you didn't spot it, that sentence uses the word "their" as a singular pronoun (agreeing with the earlier singular noun phrase "any college graduate"), which is severely frowned upon in academic English. Such instances are ironic, but it is my hope that they can also be teaching moments. If people can come to understand that their own language is never incorrect, I believe that's the first step to realizing the same thing must be true of everyone else's as well.

If you feel as I do, welcome (back) aboard the language hippie train! Go forth to tolerate and embrace linguistic variability, and feel free to use the Clippy image for your own potential teaching moments whenever you see a call for them.

And it's true: we are scientists of language, but we are also its most fervent admirers: the ones who, as Jodie says, "get REALLY excited over an aspirated p, or the history of a word, or using 'Dude' as a gender-neutral greeting." That's why we don't judge forms that aren't in line with the standard. From our perspective, that unusualness just makes them cooler! Jodie's slides make this point quite clearly and humorously, while also sharing a little bit more detail about some of the particular cool things that we study.

Speaking of responses, I also wanted to share the following image, which I originally made for use on Tumblr. (I'll try to be better about keeping this site updated, but I've been doing a lot of my language blogging on Tumblr in recent months. It enables a much more immediate and back-and-forth conversational style than the comment space on a traditional blog like this one. Whether you have an account with Tumblr or not, you can follow me there at lesserjoke.tumblr.com. Keep in mind that I don't always blog about language, though!) Here's the image, designed to look like a notification from the old Microsoft Word Assistant, Clippy the Paperclip:

I think this image speaks for itself, but I made it to respond to the many, many people who criticize someone else's nonstandard language, only to use one or more forms in that criticism that are nonstandard themselves. Of course, I think language criticism is baseless even when it's formed entirely in the standard, but I've been astonished lately at how often I've been seeing sentiments like this one: "Any college graduate who doesn't know proper English should forfeit their degree." If you didn't spot it, that sentence uses the word "their" as a singular pronoun (agreeing with the earlier singular noun phrase "any college graduate"), which is severely frowned upon in academic English. Such instances are ironic, but it is my hope that they can also be teaching moments. If people can come to understand that their own language is never incorrect, I believe that's the first step to realizing the same thing must be true of everyone else's as well.

If you feel as I do, welcome (back) aboard the language hippie train! Go forth to tolerate and embrace linguistic variability, and feel free to use the Clippy image for your own potential teaching moments whenever you see a call for them.

Thursday, December 15, 2011

On pedantry, ambiguity[,] and the Oxford comma.

Hello to all my language hippies out there! I thought I would share an infographic I made earlier today, based upon an image I keep seeing people pass around online (roughly the top left of this version). The original purports to show that the Oxford comma, which is the use of a comma before the word 'and' in a list of three or more items, removes ambiguity from writing. My own version is meant to show that there are other sentences where it is the lack of an Oxford comma which would prevent ambiguity from arising instead.

Hello to all my language hippies out there! I thought I would share an infographic I made earlier today, based upon an image I keep seeing people pass around online (roughly the top left of this version). The original purports to show that the Oxford comma, which is the use of a comma before the word 'and' in a list of three or more items, removes ambiguity from writing. My own version is meant to show that there are other sentences where it is the lack of an Oxford comma which would prevent ambiguity from arising instead.My opinion is that you should use whichever style you prefer in your own writing, but also that you shouldn't judge other people for using a different one in theirs. But if you're going to get into an argument with someone over the relative merits of the Oxford comma or its absence, make sure you have the facts on your side: neither style is inherently less confusing or more straightforward than the other. It's all just just a matter of personal preference, or what the writer thinks will be most effective in a given sentence.

Friday, November 18, 2011

Language Rules! (That's a statement, not a noun phrase.)

Question: Hey, I’m just wondering- and totally not in a sarcastic/condescending way- from a linguists perspective, if there’s no “wrong” usage of words or grammar, why have rules at all? Are there any that matter? Just wanted to get your views on it.

Answer: Linguists really do vary, and most are not as pigheadedly anti-prescriptivist as I am. =) But, from my perspective, we don’t need rules at all. English survived for quite a while before people started writing down the rules to it, and there are many societies around the world still today that don’t actively enforce linguistic rules.

There’s a huge pressure on people who directly interact to understand one another. If X and Y are going to communicate to each one’s benefit, they’re going to need to be able to successfully pass messages back and forth. And when you expand that to an entire society, the principle remains the same: the language of people who are forced to communicate naturally converges to the point of understandability, without the need for actively prescribing rules.

Due to that pressure, most variation within a language is just statistical noise: it’s interesting, it can teach us a lot about the principles of grammar, and I would even say it’s beautiful… but it’s so minor that it doesn’t get in the way of comprehension. It’s really rare for two speakers of the same language to truly not be able to understand each other.

And if that were to happen — if, without the active enforcement of grammatical rules, a formerly common language begins splitting apart… who cares? Historically, that’s happened plenty of times. The various Romance languages all descended from dialects of Latin, Old English branched away from Old Germanic, and so on and so forth. Languages split when that social pressure goes away: when one population of Old Germanic speakers no longer are interacting enough with the others to need to maintain cross-group intelligibility. It’s a perfectly natural linguistic process, and it almost doesn’t make sense to stand in its way. If we need to understand one another, we will, and if we don’t, what’s the point of making sure we can?

So that’s my answer! The explicit enforcement of grammatical rules is unnecessary and only serves to unfairly shame speakers of nonstandard variants. If we just let the invisible hand take care of it (the way many societies have done and continue to do today), an equilibrium of necessary intelligibility in language would soon be achieved.

Answer: Linguists really do vary, and most are not as pigheadedly anti-prescriptivist as I am. =) But, from my perspective, we don’t need rules at all. English survived for quite a while before people started writing down the rules to it, and there are many societies around the world still today that don’t actively enforce linguistic rules.

There’s a huge pressure on people who directly interact to understand one another. If X and Y are going to communicate to each one’s benefit, they’re going to need to be able to successfully pass messages back and forth. And when you expand that to an entire society, the principle remains the same: the language of people who are forced to communicate naturally converges to the point of understandability, without the need for actively prescribing rules.

Due to that pressure, most variation within a language is just statistical noise: it’s interesting, it can teach us a lot about the principles of grammar, and I would even say it’s beautiful… but it’s so minor that it doesn’t get in the way of comprehension. It’s really rare for two speakers of the same language to truly not be able to understand each other.

And if that were to happen — if, without the active enforcement of grammatical rules, a formerly common language begins splitting apart… who cares? Historically, that’s happened plenty of times. The various Romance languages all descended from dialects of Latin, Old English branched away from Old Germanic, and so on and so forth. Languages split when that social pressure goes away: when one population of Old Germanic speakers no longer are interacting enough with the others to need to maintain cross-group intelligibility. It’s a perfectly natural linguistic process, and it almost doesn’t make sense to stand in its way. If we need to understand one another, we will, and if we don’t, what’s the point of making sure we can?

So that’s my answer! The explicit enforcement of grammatical rules is unnecessary and only serves to unfairly shame speakers of nonstandard variants. If we just let the invisible hand take care of it (the way many societies have done and continue to do today), an equilibrium of necessary intelligibility in language would soon be achieved.

Saturday, September 17, 2011

Accepting Accents

Ben Trawick-Smith's Dialect Blog recently posted a short piece on "great minds who kept their accents." He lists, along with accompanying video clips, several renowned intellectuals who were able to achieve success despite speaking with a nonstandard and stigmatized language variety. Trawick-Smith comments:

If no accents are better or worse than any other, why do we act as though they are? And if we are interested in decreasing the amount of accent discrimination in society today, what steps can be taken to remedy the situation? As I see it, there are three broad factors that need to be addressed: under-exposure, hostile treatment, and misleading commentary.

The first factor that leads us to discriminate against people on the basis of how they sound is simply one of exposure. If we are used to a certain variety of speaking, anything different from that is going to seem unusual -- and it is all too easy to treat the unusual as incorrect. This, I think, is a natural human impulse: to treat what we are accustomed to as the norm, and any deviation as a deficit. Racists tend to have grown up without much exposure to people from other backgrounds, and I think the same can be said for people who discriminate based on accent. If we are used to everyone being similar to us, we are likely to assume that anything different must be a sign of something wrong.

The solution to under-exposure, of course, is to increase the representation of other language varieties around us, particularly for children who are growing up and still forming their conceptions of what is and isn't normal. Just as a child being raised in a multicultural environment is likely to be tolerant toward other cultures, so too would someone growing up amid a rainbow of sounds likely be open to people who don't sound exactly like themselves.

There are many possible steps toward achieving this sort of diversity. One is simply to welcome people of different backgrounds into our communities, and to foster a sense of welcomeness ourselves, so that more people will feel pride and not shame when using their natural speech patterns. Another strategy, however, is to increase the representation of different language varieties depicted in mass media, particularly those films, music, and television programs that are aimed at children. In her book English with an Accent: Language, Ideology, and Discrimination in the United States, Rosina Lippi-Green relates a study of English accent use in the 24 full-length Disney animated features released between 1938 and 1994. Among her conclusions is the following:

That people discriminate based on accent, however, is not just a reflection of representative exposure. There is also the greater issue of how language varieties are treated in society when they do appear. In that same study, Lippi-Green looked at how accent related to character motivations: what does the typical Disney 'good guy' sound like? And which accents are used to convey villainy? She concludes:

The final factor that leads to accent discrimination follows quite logically from under-exposure to diversity and unfair treatment of language varieties, but it bears mentioning independently. I am speaking here of commentary: the lessons we explicitly teach our children about language. Under-representation and skewed portrayals of language varieties can associate negative qualities with the speech of others, but the clearest way in which that message spreads is by people actually voicing the opinion to others. And once again, children are key. We cannot blame children for believing the lessons that parents, teachers, and other role models present to them as truth. But we can try, as role models ourselves, to rectify this situation. We can stop telling children there are incorrect ways of speaking, and actively inform them that differences in speech are not deficiencies. (I am speaking here primarily of accents, although I do think the same lesson applies to differences of grammar and word choice.)

I am not pretending that these strategies would be easy to carry out, or that most people would be receptive toward them. But if you believe, as I do, that it is unfair to discriminate against someone on the basis of his or her accent, then I encourage you to take such steps in your own life and in the environment in which you raise your children.

It is a sad fact that we easily underestimate people because of their accents... I’ve long hoped for a world in which we no longer associate certain accents with intellectualism. And while such a world may never be possible, it’s worth noting that genius speaks in many different voices.The major point here, of course, is that language variety is not a reliable indicator of intellectualism, and it is both unfair and unscientific to act as though it is. I've mentioned before how from an objective, scientific point of view no language form or style is inherently better or worse than any other, and it is also true that personal qualities such as intelligence cannot be linked to the way you speak. Nevertheless, people tend to act as though speech is something that can be done right or done wrong, and to discriminate heavily against those perceived as wrong. The common assumption appears to be that only one form of language is correct and that all others are wrong -- and therefore that anyone speaking differently than the standard is unintelligent. Trawick-Smith's blog post represents an excellent demonstration that language is no indication of ability.

If no accents are better or worse than any other, why do we act as though they are? And if we are interested in decreasing the amount of accent discrimination in society today, what steps can be taken to remedy the situation? As I see it, there are three broad factors that need to be addressed: under-exposure, hostile treatment, and misleading commentary.

The first factor that leads us to discriminate against people on the basis of how they sound is simply one of exposure. If we are used to a certain variety of speaking, anything different from that is going to seem unusual -- and it is all too easy to treat the unusual as incorrect. This, I think, is a natural human impulse: to treat what we are accustomed to as the norm, and any deviation as a deficit. Racists tend to have grown up without much exposure to people from other backgrounds, and I think the same can be said for people who discriminate based on accent. If we are used to everyone being similar to us, we are likely to assume that anything different must be a sign of something wrong.

The solution to under-exposure, of course, is to increase the representation of other language varieties around us, particularly for children who are growing up and still forming their conceptions of what is and isn't normal. Just as a child being raised in a multicultural environment is likely to be tolerant toward other cultures, so too would someone growing up amid a rainbow of sounds likely be open to people who don't sound exactly like themselves.

There are many possible steps toward achieving this sort of diversity. One is simply to welcome people of different backgrounds into our communities, and to foster a sense of welcomeness ourselves, so that more people will feel pride and not shame when using their natural speech patterns. Another strategy, however, is to increase the representation of different language varieties depicted in mass media, particularly those films, music, and television programs that are aimed at children. In her book English with an Accent: Language, Ideology, and Discrimination in the United States, Rosina Lippi-Green relates a study of English accent use in the 24 full-length Disney animated features released between 1938 and 1994. Among her conclusions is the following:

While 91 of the total 371 characters occur in roles where they would not logically be speaking English [such as characters in France in Beauty and the Beast, or the citizens of the mythical Arabic kingdom in Aladdin], there are only 34 characters who speak English with a foreign accent.To children, this can send a message that certain language varieties are more normal or better than others, and make it harder to treat differently-accented people with fairness. (Children who do not speak the standard Disney accent might also infer that their language varieties, and thus they themselves, are in some way inferior.) Greater representation of accent variation in Disney films would certainly help acclimatize children to the widespread diversity of language that exists in the real world.

That people discriminate based on accent, however, is not just a reflection of representative exposure. There is also the greater issue of how language varieties are treated in society when they do appear. In that same study, Lippi-Green looked at how accent related to character motivations: what does the typical Disney 'good guy' sound like? And which accents are used to convey villainy? She concludes:

Close examination of the distributions indicates that these animated films provide material which links language varieties associated with specific national origins, ethnicities, and races with social norms and characteristics in non-factual and sometimes overtly discriminatory ways. Characters with strongly positive actions and motivations are overwhelmingly speakers of socially mainstream varieties of English. Conversely, characters with strongly negative actions and motivations often speak varieties of English linked to specific geographical regions and marginalized social groups.Children are thus taught not only that certain varieties of language are more normal than others, but also that the less normal varieties can be taken as an indication of moral failing. It is only logical that individuals taught to discriminate will grow up to discriminate, and from the evidence Lippi-Green has provided, Disney is definitely teaching intolerance. Of course, such animated films are only one small facet of society, but they are nevertheless a representative look at how language varieties tend to be treated. And any time a variety is presented as substandard or its speakers are treated as such, children are learning not to treat others fairly. The solution, then, is to stop discriminating ourselves, both in our day-to-day lives and in the media materials we create for children's consumption. If our actions are being taken by children as examples of what is proper and right, then by all means, let us treat others with fairness no matter how they speak.

The final factor that leads to accent discrimination follows quite logically from under-exposure to diversity and unfair treatment of language varieties, but it bears mentioning independently. I am speaking here of commentary: the lessons we explicitly teach our children about language. Under-representation and skewed portrayals of language varieties can associate negative qualities with the speech of others, but the clearest way in which that message spreads is by people actually voicing the opinion to others. And once again, children are key. We cannot blame children for believing the lessons that parents, teachers, and other role models present to them as truth. But we can try, as role models ourselves, to rectify this situation. We can stop telling children there are incorrect ways of speaking, and actively inform them that differences in speech are not deficiencies. (I am speaking here primarily of accents, although I do think the same lesson applies to differences of grammar and word choice.)

I am not pretending that these strategies would be easy to carry out, or that most people would be receptive toward them. But if you believe, as I do, that it is unfair to discriminate against someone on the basis of his or her accent, then I encourage you to take such steps in your own life and in the environment in which you raise your children.

Tuesday, September 6, 2011

Thoughts on a New Year of School

Welcome back, students! It's a new semester at the University at Buffalo, where I have the good fortune to study and teach in the department of linguistics. Over the coming months I will be TA-ing LIN 200, Language in Pluralistic America. That course is very dear to my heart, as it focuses on matters of linguistic diversity and prejudice, which are topics I tend to blog about here. It is a class aimed at non-linguists, and serves as an introduction to the idea that differences in people's speech are not necessarily a problem to overcome (or a sign of low intelligence, laziness, poor education, and so on).

After the first meetings with my two discussion sections, I find myself reflecting on the fact that linguistics is not a field that the average person knows a lot about. There are two false assumptions about the discipline in particular that I commonly encounter, and I should expect that at least some of my students will hold them already. Some may in fact have signed up for their first linguistics class because of these assumptions, and I should be prepared to face some surprise. I'm not entirely sure of the readership of this blog, but if you are a newcomer to linguistics yourself (especially if you've found it as one of my students), this short post might help set some of the facts straight.

Common Assumption #1: Linguists speak and study many languages. By far, the most common question linguists are asked is, "Oh, how many languages do you speak?" And as a descriptivist, I have to admit that this is a legitimate alternative definition to the word 'linguist': a person who speaks many languages. But in an academic context, the word more often refers to someone who studies language for a living, regardless of how many languages they happen to speak themselves. Some of us may speak multiple tongues, but asking about that is sort of like asking a veterinarian how many pets he or she has. The answer might be more than one, but that fact is entirely coincidental to the person's profession. (For what it's worth, my kind of linguist refers to a person who can speak multiple languages as multilingual or a polyglot.)

Common Assumption #2: Linguists are there to enforce standards on languages. Language is a beautifully complicated thing, and it's true that linguists are interested in making sense of it all. But to borrow a metaphor from Erin McKean's excellent TED Talk on lexicography, that does not make us the traffic cops of speech and writing. Our goal is to accurately describe language as it's already being used, not to endorse or enforce a standard. As scientists we want to observe raw data, and dictating what that data should look like is only going to weaken the conclusions we can draw.

One final note: Because of the scientific benefit of remaining objective, almost every linguist employs a descriptive approach to the language(s) that they study. I personally identify as a linguistic descriptivist (and not just a linguist) because I consider it my obligation to extend this objectivity into public outreach and social activism. There are a lot of unfounded stereotypes and prescriptivst notions in the world today, and I try to use my education to help counter this ignorance. This blog is part of my effort to spread the fact that from a scientific point of view, everyone’s language is inherently correct. There are no wrong ways to say something, and telling someone they’re using language incorrectly can be as hurtful as saying they’re of the wrong religion, sexual orientation, skin color, etc. My advocacy for language equality and tolerance is not something that every linguist engages in, but it stems from everything I've learned as a scientific observer of language.

In general, of course, a linguist is someone who is very interested in language. So the main thing to remember, when you happen across one of us in our natural setting, is that we like to talk about talk. This means that if there's anything you've ever wondered about how language works, feel free to ask a linguist! As long as you're okay with the possibility of having your opinions challenged, then we should get along just fine.

Class dismissed!

After the first meetings with my two discussion sections, I find myself reflecting on the fact that linguistics is not a field that the average person knows a lot about. There are two false assumptions about the discipline in particular that I commonly encounter, and I should expect that at least some of my students will hold them already. Some may in fact have signed up for their first linguistics class because of these assumptions, and I should be prepared to face some surprise. I'm not entirely sure of the readership of this blog, but if you are a newcomer to linguistics yourself (especially if you've found it as one of my students), this short post might help set some of the facts straight.

Common Assumption #1: Linguists speak and study many languages. By far, the most common question linguists are asked is, "Oh, how many languages do you speak?" And as a descriptivist, I have to admit that this is a legitimate alternative definition to the word 'linguist': a person who speaks many languages. But in an academic context, the word more often refers to someone who studies language for a living, regardless of how many languages they happen to speak themselves. Some of us may speak multiple tongues, but asking about that is sort of like asking a veterinarian how many pets he or she has. The answer might be more than one, but that fact is entirely coincidental to the person's profession. (For what it's worth, my kind of linguist refers to a person who can speak multiple languages as multilingual or a polyglot.)

Common Assumption #2: Linguists are there to enforce standards on languages. Language is a beautifully complicated thing, and it's true that linguists are interested in making sense of it all. But to borrow a metaphor from Erin McKean's excellent TED Talk on lexicography, that does not make us the traffic cops of speech and writing. Our goal is to accurately describe language as it's already being used, not to endorse or enforce a standard. As scientists we want to observe raw data, and dictating what that data should look like is only going to weaken the conclusions we can draw.

One final note: Because of the scientific benefit of remaining objective, almost every linguist employs a descriptive approach to the language(s) that they study. I personally identify as a linguistic descriptivist (and not just a linguist) because I consider it my obligation to extend this objectivity into public outreach and social activism. There are a lot of unfounded stereotypes and prescriptivst notions in the world today, and I try to use my education to help counter this ignorance. This blog is part of my effort to spread the fact that from a scientific point of view, everyone’s language is inherently correct. There are no wrong ways to say something, and telling someone they’re using language incorrectly can be as hurtful as saying they’re of the wrong religion, sexual orientation, skin color, etc. My advocacy for language equality and tolerance is not something that every linguist engages in, but it stems from everything I've learned as a scientific observer of language.

In general, of course, a linguist is someone who is very interested in language. So the main thing to remember, when you happen across one of us in our natural setting, is that we like to talk about talk. This means that if there's anything you've ever wondered about how language works, feel free to ask a linguist! As long as you're okay with the possibility of having your opinions challenged, then we should get along just fine.

Class dismissed!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)